In November every year, Zimbabwe’s second-largest city, Bulawayo, explodes into a magnificent riot of colour as the majestic purple jacaranda and the flame-red flamboyant trees bloom, transforming the wide tree-lined streets into a glorious spectacle.

But beneath this blissful veneer of blossoms is a troubled city struggling to come to terms with a devastating shortage of water and the resultant loss of life.

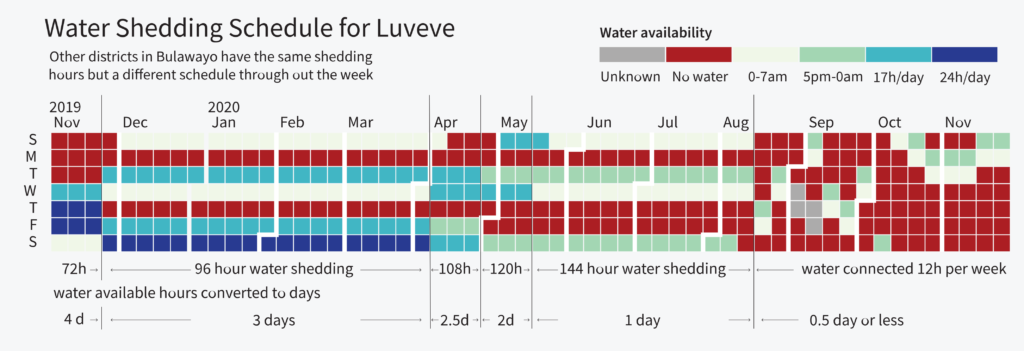

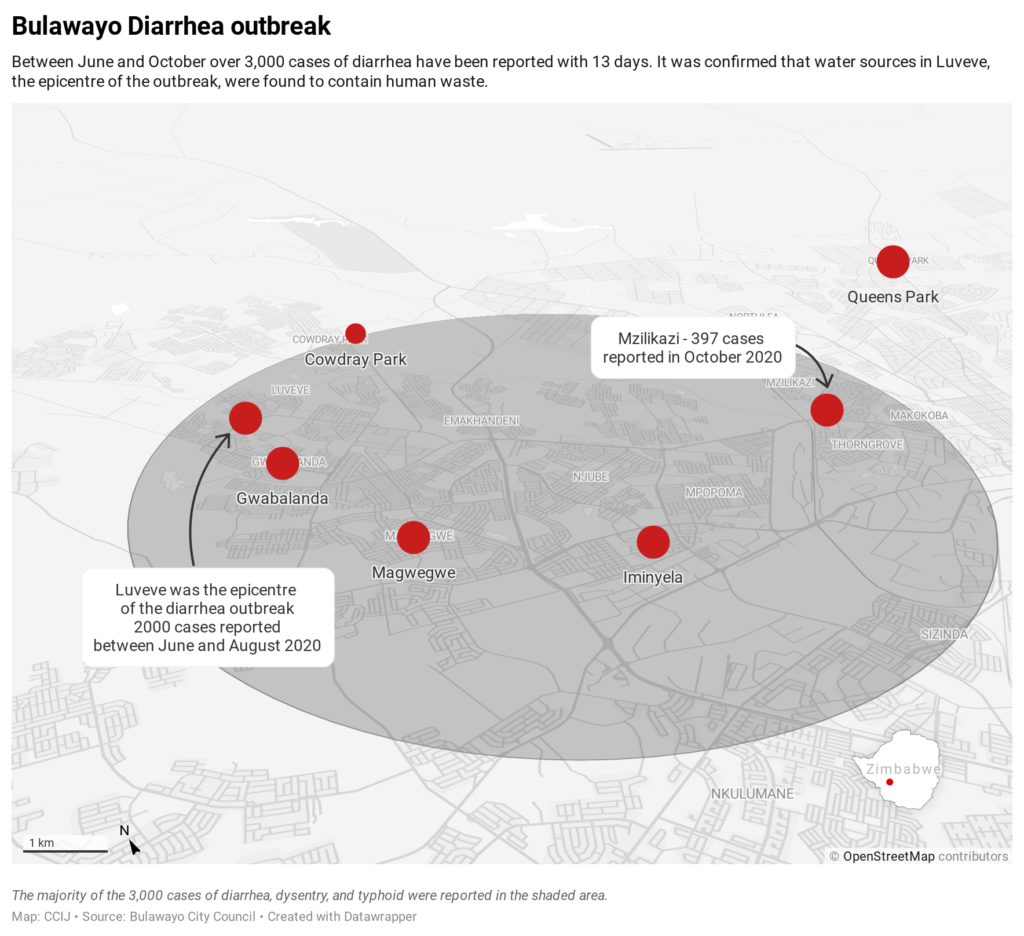

In June, three months into a Covid-19 lockdown, Bulawayo was blindsided by a totally different disease—diarrhea.

The gastro-intestinal malady, which spreads through the ingestion of contaminated water and food, had killed 13 people by July and infected more than 2 000 others. Some of the survivors suffered mysterious skin disfigurement. And many are yet to settle their hefty medical bills.

The Bulawayo Municipality said eight suburbs were affected. In September, city clinics were attending to more than 240 cases of diarrhea every two days. In comparison, Covid-19, at that time, had claimed six lives.

“The diarrhea outbreak caught many of us by surprise. We were bracing for a Covid-19 emergency, like everywhere else in the world. I can’t adequately describe the terrifying sense of fear and shock caused by the diarrhea outbreak under the shadow of the Covid-19 crisis,” recounted Mthokozisi Sibanda, a city resident.

Diarrhea killed 13 people by July and infected more than 2 000 others.

The sprawling townships of Luveve and Cowdray Park was the epicentre of the diarrhea outbreak. Local residents recounted the ordeal of having to constantly dice with death, as the twin perils of Covid-19 and water-borne disease stalked the area.

The diarrhea-related deaths have since subsided, but emotional scars remain fresh, worsened by a water shortage that threatens to spiral out of control.

But even as that threat lessened, deaths in the city attributed to the coronavirus have increased in October and November. The increased toll from the virus comes amid warnings from Solwayo Ngwenya, a local professor of medicine and clinical director of Bulawayo’s largest hospital, that the reluctance of residents to wear face masks has increased the risk of a “second wave” of infections.

Climate change is real

Three out of six water-supply dams have dried up owing to dwindling rain, forcing the municipality to introduce drastic rationing which has seen most suburbs receiving water for only 12 hours over an entire week.

The director of the Bulawayo City Council’s department of engineering services, Simela Dube, made the chilling revelation that Criterion Water Works, a giant reservoir holding 10 days’ buffer storage, has now completely dried up.

“It’s the first time in history,” Dube said. “The issues of climate change are starting to show. The inflows into our dams continue to decline almost every season.”

The city’s 650 000 residents need at least 150 megalitres (150 million litres) of water a day, but the municipality can supply only 89 megalitres, using five bowsers – tankers – for transporting water.

The huge disparity between supply and demand means people are forced to resort to unsafe sources of water, such as unprotected wells, contaminated streams and boreholes whose water quality is questionable.

Photo: Zinyange Auntony

Bulawayo City Council (BCC) says laboratory tests have ruled out fears that the diarrhea is caused by serious notifiable diseases such as cholera, typhoid and dysentery. Municipal health officials attribute the outbreak to residents’ poor hygiene practices, particularly the use of dirty water-storage containers.

Civic groupings have challenged this narrative, accusing the city council of supplying “tainted” water.

In the face of the mounting crisis, the municipality has sought permission from the central government to conduct a study to establish whether it would be feasible to allocate each household the first 5 000 litres of water for free every month, according to Dube. It is an ambitious “pro-poor” plan.

He says the study—which will also look into the viability of the water-tariff structure—will cost US$600 000.

“The study will also look into the ring-fencing of the water services so that water can account for its own expenditure and income without getting subsidies from other (municipal) accounts.”

Finding clean water is tough

Mother-of-two Anna Nduna, 21, said it has become very difficult to juggle the tasks of tending to her three-month-old twins while also frantically hunting for water.

“I am staying in Cowdray Park and the water situation there is very dire. Sometimes we spend three weeks without (municipal) water. Due to that, we ended up resorting to fetching water from unprotected wells near the [spilled] sewage,” she said.

“To make matters worse, I have three-month-old twins. So, I struggle to get water for washing their nappies and for cooking. I come here (looking for water) every day, two or three times a day. Today, I have been here since 1pm and now it’s already 4pm,” she said while attending to her crying babies.

The distance between her home in Cowdray Park and where she fetches water is about a kilometre.

Asked how she manages to carry a 20-litre bucket of water plus her twin babies, she said: “I strap one of my babies to my back and the other one in front. There is nothing I can do. The situation is horrible and unbearable.”

Her husband works as an illegal artisanal gold miner in Inyathi, 68 kilometres from Bulawayo and the family’s modest income does not afford her the luxury of buying borehole water from private suppliers.

Tormented by a running stomach

Sikhathele Ncube, 43, a mother-of-three and resident of New Luveve township, said diarrhea is terrorising her family.

The water situation in Luveve is unbearable for residents, made worse by a burst pipe that was spewing untreated effluent close to where many residents collect water when I visited the area.

“We fetch water near the sewage because we don’t have options,” Ncube said, referring to a nearby broken pipe that was spewing raw effluent when I visited the area.

“We wake up at 2am to queue for water at the wells here,” said Ncube. “I use this water for cooking, drinking and washing. Just look at that,” she gestured, pointing at a nearby pile of human waste.

“People are sick with diarrhea and other water-borne diseases. As I speak, I have a running tummy, and so do my children. We don’t care whether the water is safe or not,” she said.

It takes her an agonising 40 minutes to fill up a 20-litre bucket.

“We fetch water near the sewage because we don’t have options.”

Sikhathele Ncube

“What we need is water for drinking and cooking. We wonder what will happen now the schools have opened. My children last had a bath a week ago. With the outbreak of Covid-19, we don’t know how we can protect ourselves from it since we don’t have water to wash our hands regularly. Toilets are not being flushed. Everything is just messed up,” Ncube lamented.

Fistfights routinely break out when desperate residents jostle to fetch water at unprotected wells, she added. “Sometimes we fight over water, something which is very terrible.”

Women live in fear of sexual violence

Women are also fearful of being mugged or raped while hunting for water in the dark, according to Ncube. But it was “better to be mugged than to die of thirst,” she said.

“Yes, we can be raped, but what is more important to me is to provide water for my children. We are between a rock and a hard place.”

Sibonokuhle Nyoni, 38, a mother-of-two from Old Luveve township, also believes that the dire water shortage was exposing women and girls to sexual violence.

Nyoni travels six kilometres from Old Luveve to another suburb, Emakhandeni, to access water from a borehole.

“Water is life and if you don’t get it, then it means there is no life. We are afraid of disease outbreaks. We wake up at 4am looking for water. We come here twice a day,” Nyoni said.

To protect themselves from knife-wielding muggers, women walk in groups.

“The situation is terrible, especially for women. For instance, some women are nursing babies and they need water for washing nappies and cooking for their children,” said Nyoni. “But with this water situation in Bulawayo, it becomes very difficult for them.”

Nyoni said they spend most of their productive time looking for water.

“We always think about water, nothing else, and this is affecting our day-to-day lives. You can’t do other things,” she said.

Photo: Darlington Mwashita

Muggings, fistfights and rape are not the only perils encountered in the hunt for water. Sikhangezile Ndlovu, 37, a mother-of-three from New Luveve township, who has dug a well in her backyard, lives in constant fear that her children may accidentally fall in and drown.

In a bid to solve her water challenges, Ndlovu dug the three-metre-deep well in August. But it is not covered, exposing her children to danger.

“Since I came here in August from South Africa, I have never received water from the city council. So, we decided to dig a well at our house. The well has been very helpful and my neighbours also come and fetch water from here,” she said.

Tackling crisis through advocacy

Following the diarrhea outbreak, which has so far claimed 13 lives, residents of Luveve township formed a “water crisis committee.” It includes their local councillor, Member of Parliament, and residents. The aim is to urgently find solutions to the water crisis.

One of the committee members, Chrispin Ngulube, 62, a survivor of the devastating diarrhea, said they teamed up with other stakeholders and approached the High Court in Bulawayo. They were seeking an order directing the city council to release laboratory samples of tap water and other vital information pertaining to the disease outbreak.

Photo: Darlington Mwashita

However, the residents withdrew the lawsuit after the municipality indicated willingness to release the information.

The initial intention of the residents was to invite a private laboratory in Harare to subject Bulawayo’s municipal water samples and pipes to stringent tests.

“When the diarrhea outbreak began, the council did not take it seriously. In fact, they accused residents of using dirty water containers for storing water. Things got worse and people started dying in [significant] numbers, prompting the residents to take action,” Ngulube said.

“Due to the water crisis, we lost lives, both young and old, in Luveve. We still have people who are having problems even after the outbreak. My wife and I were also affected by diarrhea. We nearly died. I had a running tummy and stomach cramps and I had to go to Luveve Clinic.”

In a separate lawsuit four months ago, some Bulawayo residents filed a class action lawsuit at the High Court, suing the city council and central government for failing to fulfill their constitutional obligation to supply adequate water.

Council spokesperson Nesisa Mpofu refused to comment on the case, describing the matter as sub judice (before a court).

Speaking out

Ishmael Mkandla, another member of the residents’ committee, said advocacy could make a difference in communities by raising awareness and mobilising assistance.

“We appealed for assistance in different organisations, both legal organisations as well as residents’ organisations. We received a lot of donations and distributed them to the affected residents. There is also another organisation which has drilled a borehole with the help of the local Member of Parliament, Stella Ndlovu, to assist the communities.”

Recently, 1 374 residents of Bulawayo`s Luveve township signed a petition addressed to their councillor, Febbie Msipa, demanding an urgent solution to the water shortage. They also complained that many houses no longer receive piped water even when supplies are restored during the 12-hours-per-week window.

Semukele Mnkandla, vice-chairperson of the Bulawayo United Residents’ Association in Luveve township, said she suffered from a running stomach for almost a month after drinking contaminated tap water.

“I spent the whole month not feeling well after being affected by diarrhea. Diarrhea affected both children and old people. What I can tell you is that some of these people who were affected are still sick even today,” she said.

“They are having skin diseases. There is a young man aged 21 whose intestines got twisted and, as a result, he is now using a tube when he wants to relieve himself. His system got damaged. This has even forced him to change diet,” she said.

Those who were ferried to hospital by ambulance are also personally responsible for hefty bills which are accumulating interest, she said.

How safe is municipal water?

Bulawayo mayor, Solomon Mguni, said the city’s municipal water is clean.

“Every effort is made to supply the residents with clean safe water at all times. Despite the initial quality of water after treatment, it from time to time gets contaminated during distribution, transportation and storage due to unhygienic storage and handling practices,” he said.

The city council has encouraged residents to ensure the storage containers are clean and to boil the water before consumption.

The municipality’s director of health services, Edwin Sibanda, said the piped water is safe for consumption, even though it emits an unpleasant odour and has an unusual colour—especially soon after supplies are restored following the drastic rationing measures.

Sibanda argued that the strange smell is not a danger to human health, but some residents have refused to accept this official explanation.

Waterpreneurs cash in

The city’s deputy mayor, Mlandu Ncube, said the municipality has no solution to the crippling shortage of water and is now pinning its hopes on early and bountiful summer rains.

The city council has tried to lessen the suffering by delivering water by bowser. There are five bowsers, four of which have a volume of 18 000 litres each and the fifth one carries 10 000 litres. Community leaders say this is woefully inadequate to cater for 650 000 residents.

Enterprising “waterpreneurs” are cashing in and selling water. They use tanks and browsers to fetch water, often from boreholes located on private property, and sell it to desperate residents. To run such a water-supply business, one must have authorisation from the Environmental Management Agency, but most “waterpreneurs” operate illegally. The borehole water is being sold for up to US$43 for 5 000 litres. In a country where the United Nations says 60% of the entire population faces starvation and extreme poverty is on the rise, most people in Bulawayo—many who earn less than US$100 per month—simply cannot afford to buy water at those prices.

Triple whammy hits Bulawayo

Residents are grappling with a triple whammy that has made it extremely difficult to access potable water: dwindling rainfall as drought and climate change take their toll; decaying water supply infrastructure; and a sharp increase in cases of water-borne diseases.

The loss of lives to such a primitive ailment has brought untold humiliation upon Bulawayo, once regarded Zimbabwe’s best-run city.

A neatly designed metropolis with ornate colonial architecture, its iconic avenues were built wide enough to allow a span of 16 oxen and a cart to make a full turn. It was established by the King of the Northern Ndebele, Mzilikazi Khumalo, King Shaka’s military general who famously fled Zululand and founded the Mthwakazi kingdom. Mzilikazi’s son and successor, King Lobhengula, would later be defeated by British imperial invaders.

By June 1894, a modern town was taking shape. The country’s first stock exchange was built in Bulawayo. Economic historians attest to the fact that Bulawayo had electric lighting in 1897, way before London did—a remarkable feat. Bulawayo’s nickname is “City of Kings”.

The water crisis is a sore point for local residents, who see it as a blemish on this proud heritage.

An ancient crisis implodes

The perennial shortage of water dates back to 1912 when the British colonial settlers first mooted the ambitious idea of laying a 400-kilometre pipeline to draw water from the Zambezi, Africa’s fourth-longest river.

The tantalising idea has enchanted generations, but remains a pipe dream. The Zambezi—the longest east-flowing river on the continent and the largest African river emptying into the Indian Ocean—is viewed as the only lasting solution to arid Matabeleland’s water woes.

But for decades, politicians have used the water crisis as bait to persuade gullible voters while paying lip service to the proposed Zambezi pipeline project.

Zimbabwe’s collapsing economy, described by Johns Hopkins University economist Steve Hanke as the first country to suffer hyperinflation in the 21st century, has meant that the national government lacks the financial resources to provide new sources of raw water to Bulawayo. It has also seen a rapid deterioration in the crumbling network of outdated water supply pipes.

Gwayi-Shangani Dam project

Construction of the 634-million-cubic-metre reservoir, located 245 kilometres from the city, is described by officials as the first phase of central government’s flagship solution to Bulawayo’s perennial water crisis. Its volume is almost double the combined capacity of Bulawayo’s existing dams.

After a long delay in the commencement of construction, some progress has been registered in the engineering works, amid disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Judith Ncube, the Minister of State for Bulawayo, said the dam is now expected to be commissioned in December 2022, rather than the initially planned December 2021.

Construction of the US$120 million dam is being undertaken by China International Water and Electric Corporation (CWE), a subsidiary of China Three Gorges Corporation (CTE).

When the dam is built, one pipeline will link it to the Zambezi River, while another pipeline will channel the water to Bulawayo. The total cost is estimated at US$864 million, a massive financial outlay for a broke government whose total annual national budget has rarely exceeded US$4 billion in recent years.

The government has also allocated 205 million Zimbabwean dollars (US$2.5 million) for the drilling and rehabilitation of a network of boreholes which currently supply water to residents as a stop-gap measure.

The Bulawayo City Council also took out a US$33 million loan from the African Development Bank to finance a Water and Sewerage Services Improvement Project.

The money will fund the rehabilitation and upgrading of water purification facilities, water distribution, sewer drainage network and the wastewater treatment disposal system.

Real risk of new disease outbreaks

A new report by Zimbabwe’s Auditor-General Mildred Chiri warns that Bulawayo is at risk of more water-borne disease outbreaks resulting from a failure by the municipality to manage the sewer reticulation system.

Decades of inadequate spending on public infrastructure have ensured that even when water is available a lot of it is lost as the ageing pipes are prone to frequent bursts.

Municipal finances are in shambles and my investigation revealed that the city council will increasingly find it difficult to access similar funding in future.

An analysis by a civil society organisation, the Bulawayo Progressive Residents’ Association, of council books for the seven months to July 2020 shows that the municipality’s wage bill now constitutes a massive 58% of total council expenditure, almost double the state-recommended 30% threshold.

The local authority’s governance shortcomings have come under scrutiny. Investigations by Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission investigators recently led to the arrest of the city’s director of housing, Dictor Khumalo, on charges of flouting tender and procurement procedures.

Passing the buck

Councillors and municipal officials blame the central government for failing to ensure adequate supply of bulk water to the local authority.

According to the Water Act, it is the responsibility of the central government to build dams and supply raw water to municipalities. It is the responsibility of municipalities to treat and distribute the bulk water.

We obtained video footage showing that some desperate Bulawayo residents are resorting to vandalising council water pipes. They argue it is the only way they can get water in certain suburbs.

But, from a governance perspective, it creates a vicious cycle as the municipality must spend scarce financial resources to repair vandalised pipes.

Ultimately, Bulawayo’s devastating water shortage can only be solved through the concerted efforts of the central government, the municipality, residents and other stakeholders.

Diarrhea has already claimed 13 lives. Covid-19, whose effective prevention is also dependent on access to clean water, had killed 66 people in the city by mid-November.

So, lives are at stake and urgent action is necessary before more people die from what is an avoidable disease.

This investigation was developed with the support of Wits University.