CAPE TOWN – Dams supplying Cape Town are full now but the memory of punitive water tariffs and flow restrictions for households using more than 10,5kl a month remain fresh. In the aftermath, it has emerged that while households were targeted, the City treated big industrial users with kid gloves.

Cape Town’s top ten water users sucked up billions of litres of drinking water for business as the city’s biggest dam, Theewaterskloof, edged toward an unusable 10 percent.

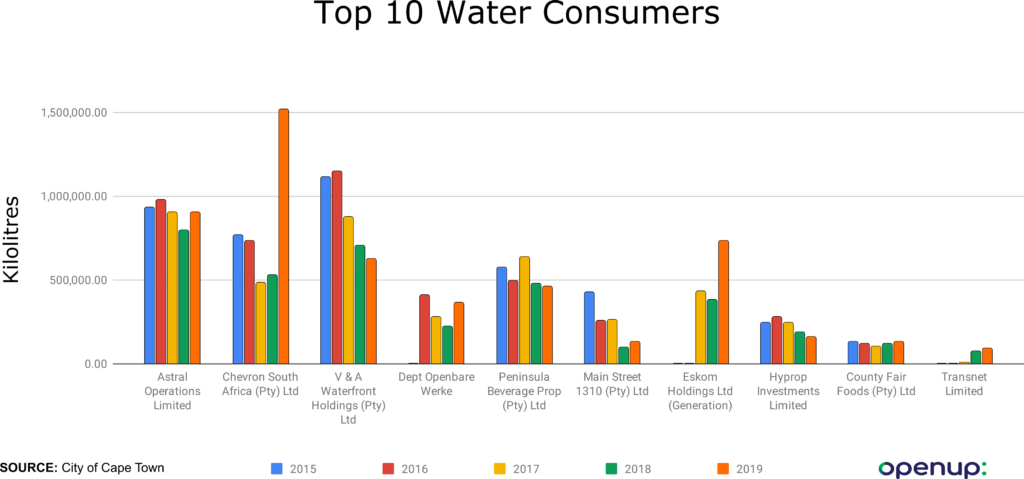

These ten companies were responsible for using 4.2 billion litres of water in 2017, and 3.6 billion litres of water in 2018, in the lead up to, and during fears of an imminent Day Zero when the City’s taps would run dry.

Data showing the ten companies’ water billings has been obtained from the City of Cape Town after a successful Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) application and a subsequent drawn-out battle for clarity on the information supplied.

The figures for the years 2015 to 2019 show that most of the companies did decrease their municipal drinking water consumption during the two most desperate years – 2017 and 2018 – as a response to City messaging.

But of the top ten water users, only Twinsaver, the makers of tissues and toilet paper – registered as Main Street Holdings 1310 – met the provincial directive to reduce consumption to 45% of pre-drought (2015) levels.

Part of the directive, which was published on 1 December 2017, was that if the companies could not reduce their water consumption to the prescribed level, they needed to provide a motivation to the City to justify their higher usage. Failure to do so would constitute a criminal offense under the City’s own Water Bylaw and companies could be fined and have a water management device installed at their premises to restrict flow.

However, no businesses were penalised for not meeting the directive.

Households using more than 10,5kl per month were investigated and their flow restricted with a water management device, which many had to pay for out of their own pockets.

In emailed responses to questions the City’s mayoral committee member for water and waste, Xanthea Limberg has stated: “Although we never took the drastic step of restricting water to any business, the steep rise in tariffs under level 6 meant that businesses were already making every effort to reduce where possible, and were penalised financially for overuse.”

However, when 6B water restrictions were imposed, industrial users only experienced a 104% increase in tariffs, from R27,77 to R57 per kilolitre – and they paid the same amount per kilolitre no matter how much they used.

Households, on the other hand, were subjected to punitive stepped tariffs, with a 556% increase at the lowest “step” of 0kl to 6kl, from R4.56 to R29.93 per kilolitre, and a 195% escalation in price, from R17,75 to R52,44 per kilolitre of usage between 6kl and 10,5kl.

Households using more than 10,5kl per month were investigated and their flow restricted with a water management device, which many had to pay for out of their own pockets.

The City was installing so many water management devices that their January 2018 budget adjustment called for an additional R10m to be used to prevent a backlog for the installation of new, customer-funded water meter devices.

Limberg’s reason for not instituting the provisions of the provincial directive against businesses was “to ensure the water crisis did not turn into a jobs crisis”.

She said in 2018, when water restrictions were at their highest, commerce and industry were responsible for 19% of all water used, with households responsible for 68%.

One company that increased usage in the critical year of 2017, despite, according to Limberg, having been warned of the need to reduce consumption, was Peninsula Beverages, which holds the licence to manufacture Coca-Cola products in Cape Town.

Their 2017 consumption of 638,7 million litres was more than the 572,2 million litres they used in 2015 before the onset of the drought.

It was only in early January 2018, according to Peninsula Beverages spokesperson Priscilla Urquhart, that the company sunk boreholes to reduce their reliance on municipal water, with water use licenses for the boreholes granted in May that year, once the threat of Day Zero had passed.

Their 2017 consumption of 638,7 million litres was more than the 572,2 million litres they used in 2015 before the onset of the drought.

Besides Peninsula Beverages, two companies that reduced their water consumption least during the critical 2017 and 2018 years, were Astral Operations, and County Fair Foods. Both are poultry producers – County Fair is a subsidiary of Astral

Neither company responded to questions sent more than a week prior to publication, despite County Fair providing an email read receipt.

As two why Eskom’s figures only begin in 2017, unsigned correspondence from their media desk states it is due to the City issuing a new water meter following a consolidation of two properties at the Koeberg nuclear plant.

But Eskom states 2016 saw an 11% reduction from 2015 water, with 2017 seeing a 26% reduction from 2015, and a 30% reduction in 2018.

The reason for usage increasing again in 2019 was because their temporary groundwater desalination plant was decommissioned due to the unreliable quantity and quality of groundwater, coupled with “a shutdown of one of the units on 2 May 2019 due to a condenser tube leak”. In addition, Eskom said “the failure of a temperature controller to appropriately control cooling of one of the sumps” led to an increase in water usage at the plant.

The threefold increase at the Astron Energy oil refinery (formerly Chevron) to a massive 1,5 billion litres in 2019 as Cape Town was still emerging from the drought, was because the water they usually took from the neighbouring Potsdam Waste Water Treatment Works (WWTW) was of such poor quality they could not run it through their own reverse osmosis plant, as was usually the case, said spokesperson Suzanne Pullinger.

Failures at the Potsdam WWTW, leading to the release of untreated or partially treated effluent, has also resulted in severe pollution of the Milnerton Lagoon, into which it is released.

Limberg has confirmed receiving a directive on 21 September from the Environmental Management Inspectorate, known as the Green Scorpions. According to James-Brent Styan, who is the spokesperson for Western Cape Minister of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning Anton Bredell, the directive orders the City to address the pollution and “accelerate some of the measures” previously submitted in their action plan.

The City is appealing the directive.

Along with Astral Operations and County Fair, the Department of Public Works, and Transnet did not respond to questions.

This investigation was developed with the support of the Money Trail Project, JournalismFund.eu and the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

A version of this story appeared in the Mother City News community newspaper and in Daily Maverick 168.