Many friends and colleagues ask me why I am deeply concerned about water issues in Iraq, while the social crises, political instability and protests surround the country from all sides. I have often answered this question verbally, by telling my own story with water, which is in fact the story of more than one billion people coping with thirst today, is directly related to human nature in terms of relation between man and his environment and the means of organizing it. My narration is a part of the solutions that we’re looking for today to avoid thirst and hunger, and it is about a one man’s loving relationship with the mulberry tree that stood beside his small house after he got married and separated from his grandparents’ house.

I was born in that small house, I saw the mulberry tree my father had brought from another village and planted in our new home. Just beside the tree, he dug a well that we never drank from. The tree did not drink from it either, because the water never flowed. Once we grew up, my dad closed up the well up, but the tree didn’t stop to growing.

Our village was, and still is, located in Garmian region, which is an arid area, and one of the flattest areas in Iraqi Kurdistan.The only water source that quenched our thirst and our loneliness were wells and a river called Awespi or white river.

In the village that seemed out of time, and was completely destroyed during the Anfal genocide against the Kurds by Saddam Hussein’s regime in 1988, no one was taught how to manage the scarce resources.

Water was managed through an organic and sensitive relationship between the people and the arid environment nature that our ancestors had chosen to live in. Every family had a well, and it became common to plant a mulberry tree and some reeds next to it. The mulberry did not need large amounts of water, and when we were children we were happy with the sweet white berries in the summer. The relationship between the water that we drew from the wells after long effort and our thirst required such knowledge of trees and their need for water.

Although our well did not fill with water, the mulberry tree grew, the length and branches passed through the walls of the house, which also grew up and did not remain small. My father used to water the tree with the water he used to wash with before praying every day. I never saw him wasting the water used for ablution. In this way, he recycled water and watered our beautiful tree, which attracted many types of birds and turned our home into an attractive nesting area. In his footsteps, we learned to conserve water, recycle it for watering or other uses other than drinking, fetching food and cleaning. The villagers reused the water that left over from domestic animals for gardens and vegetation

We were guardians of water and defenders of its existence and rights, and our relationship with it, did not accept pollution and rights abuse. For example, we used the White River, about an hour’s walk north of the village, without fear or hesitation for drinking, fishing and swimming, because it was pure and fresh. Quite simply, the river served us food, a sense of security and stability. These are the reasons we protected it and its rights, though these rights had not been formally recorded anywhere. There is, for example, New Zealand’s River Rights Regulations issued in 2017, but we never thought that we needed a law or a list of obligations to protect a river which was considered a part of us. It was unthinkable for us to throw anything into our water sources, our rivers, streams and wells, or in the few springs that quenched our thirst and that of birds and wild animals.

In short, before drinking and watering, our relationship with water was characterized by a kind of natural sense or poetic view: we could see the water virtually, through trees, vegetables or fruits. We knew that we could make the flavor of radishes or onions sharp by reducing water in the final stage of ripening, while we increased the amount of water if we wanted them sweet. Summer orchard, was another method of greening the wasteland, the small seedlings that we planted in spring time stored the rain for months and quench our thirst through fresh fruits.

And therefore, our water management and the ways to benefit from it drop by drop, were based on an organic relationship to nature, which revolves in an ecosystem that does not make any mistake in terms of harmonizing its elements in a renewal natural system. Our houses built of mud and their small windows, our dependence on cereals, vegetables and fruits that depend mainly on seasonal rains and our majestic river, our use of available groundwater to the extent possible, recycling of wastewater and composing reusable organic elements, residual water from streams allocated for livestock and animals for limited household farming, or for construction and repair. All these things colored our lives in harmony and continuity. And therefore, we were born guardians of water.

This instinct did not remain only in the framework of awareness of protecting fresh water, but was part of other details surrounding virtual water and wastewater, or sources of pollution that could contaminate drinkable water on the ground. Each family collected human and animal waste and the remaining ashes from burning dung and wood and put them in a place close to the house. A year later, those materials were transformed into natural fertilizer for summer farming on the banks of our only river.

Our guarding of water was a spontaneous and organic adaptation to our environment without harming the nature from which we were taking and given. We trapped spring rains in the Daim orchards to enjoy summer fruit as green water on our dry land, while today groundwater is destroyed to water the orchards and produce the fruit itself. The question here is, has humanity lost the wisdom of dealing with nature, and can we restore that innate relationship acquired by man from nature itself?

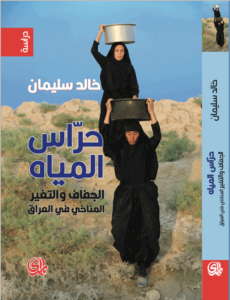

Water Guards: Drought and Climate Change in Iraq

By Khaled Sulaiman